WHEN 29-YEAR-OLD Bryan Obonyo decided to record his reaction to Santi and Ogunsi’s “Fear” with his friends in 2018, he didn’t imagine that they would go on to be a part of YouTube’s African creator community.

“I was looking to watch a reaction video of Afrobeats songs by an African YouTuber, but I couldn’t find any, so my friends and I decided to become the representation we wanted and took it upon ourselves to create a reaction video to our favorite songs,” says Obonyo. “From there on, we found an engaging audience, and now it’s our full-time job to react to new music, sometimes even with the artists themselves.” Obonyo and his friends are the proud owners of the Ubunifu Space, which has over 300 thousand subscribers and 200 million views on YouTube.

The rise of Afrobeats in recent years has coincided with the growth of Africa’s internet culture, especially on platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok. The culture of dance videos—challenges and general routines—orchestrated by Afrobeats artists has also contributed greatly to their success and helped them cultivate a diverse fan base across countries. Songs like “Love Nwantiti”, “Pretty Girl”, “Jerusalema” and more have used dance challenges to help increase the streams and impressions while promoting the creativity of African dancers, creators, and choreographers.

For 23-year-old dancer and creator Queen Olu, based in the U.S., creating content with Afrobeats helped her find a loving community with whom she shares the same interests. “I realized early on that when you combine African swag and culture with up-to-date Western influences on the internet, well, you’ve got a winning formula on your hands,” she says. “With every video I make, I find myself loving my culture more and helping spread Afrobeats to a wider audience. A lot of people don’t realize how dependent the Afrobeats industry is on creators and internet culture. I don’t just make dance videos and memes, I help records succeed.”

However, this relationship is not without its complexities. The democratization of music distribution enabled by the internet has led to concerns about copyright infringement and fair compensation for artists and creators alike. Additionally, the rapid circulation of music online can sometimes outpace traditional revenue streams, posing challenges for artists seeking to monetize their craft.

According to research from Data Company Luminate in 2023, Afrobeats fans spend 121 percent more money on music categories per month than the average U.S. music listener. Aside from viral dance challenges, lyric videos, instant remixes and memes have also flourished online, forming a wider range of user-generated content that continuously redefines the genre’s boundaries. From the Azonto craze and Shaku Shaku phenomenon in the early 2000s, digital memes have always driven the evolution of Afrobeats in unexpected directions.

Jocelyn Muhutu Remy, Spotify’s Managing Director for Sub-Saharan Africa, has seen firsthand the impact of internet culture on the genre. “Internet culture has become a vital channel for the dissemination of Afrobeats music, facilitating its rapid spread and transcending geographical boundaries,” says Remy. “On Spotify, Afrobeats streams have grown by 550 percent since 2017, with audiences in Brazil just as likely to stream Afrobeats music as those from India and the U.S. At the heart of this relationship lies the symbiotic and transformative interaction between artists, fans, and digital platforms. Afrobeats artists leverage social media to engage directly with their audience and in return, fans reciprocate by generating buzz through likes, shares, and comments, effectively amplifying the reach of the music.”

Obonyo agrees with this sentiment, sharing, “I have had a lot of my videos taken down by YouTube and the record labels because of copyrights; the revenues on a large number of my videos is split between me and the artists as their royalty. On the other hand, I’ve seen cases where a song goes viral on social media but it barely translates to streams and visibility for them. They end up losing out on being able to properly monetize their craft so I understand why they’d choose to collect royalties from creators if they can. But this can be very daunting for upcoming creatives in the space. I hope as the digital landscape continues to evolve, so too will the dynamic interplay between Afrobeats and the online world to help shape a better future trajectory.”

In 2023, an inaugural class of African YouTubers and singers like Gyakie, Asake, BNXN, Korty EO, Taooma and more received grants for the development of their content and to help improve diversity through the 23rd YouTube Black Voices Fund. But other platforms have yet to catch up, as Ola wants TikTok and Instagram to put in the effort for creators like her: “TikTok creators in Nigeria cannot monetize their accounts so when they promote these songs through challenges and memes, they are the least beneficiaries. Although many artists are paying creators to promote their music, there is still a long way to go for the appropriate revenue we should get. Meanwhile, Instagram has yet to catch up with Africa’s internet presence at all; there isn’t as much opportunity for creators like me to shine and there is a huge lack of community all around.”

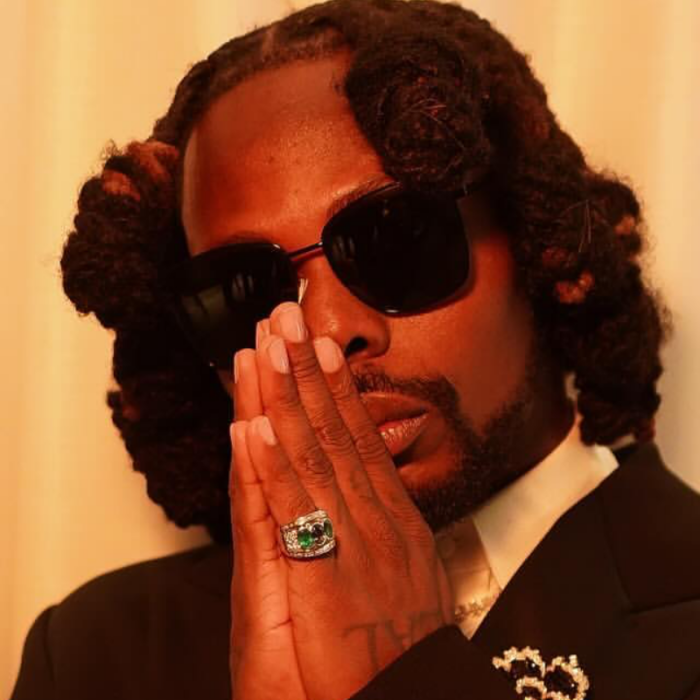

That’s what a lot of listeners likely say after hearing Veeze. His artfully parched voice is somewhat in the same lane as artists like the late Drakeo the Ruler and Young Slo-Be, but while those artists have been liable to punch through their oft-murky production with random lucidity for emphasis, the Veeze experience is exclusively croaky, offering a new take on what the quintessential “too cool” rapper can sound like. His vocal presence is as withered as Rakim’s was smooth, and yet it works for him. And his technical lyricism and eagerness to switch up cadences means that calling his sound “lazy” doesn’t do it justice. Veeze says that even as a rap fan, an artist’s voice means “a lot” to him.

“Some people’s voices are so exclusive, that’s what make the type of artist they [are],” he reasons. “Even if it’s the way they make their voice when they’re in the studio, just to make yourself poke out. That’s one of the things the fans really like, the way they’re approaching not sounding the same as any other rapper. It means a lot to me how I approach it.”

When I ask if he, as a rising artist, feels any pressure to shift his sound to seek more mass appeal, he says no. “In today’s industry, I don’t see no difference from an independent artist to a major artist,” he says. “Everybody [does] the same thing. It ain’t like it’s super talented people out here left and right. It ain’t that many Andre 3000s or Lil Waynes or people like Future… Right now, in this industry, I don’t really see nobody that I could say is sacrificing a sound to be commercial. It ain’t really a crazy high bar to reach. I feel like, in today’s world, if you work hard enough, anybody can get a No. 1 record.”

“We just be doing shit,” he says. “Sometimes I do a couple songs, sometimes I only do one song. Sometimes I do five songs. I work every day though, so I make a boundless amount.” Hopefully, the new artists around him are taking notes.

© Copyright Rolling Stone Africa 2024. Rolling Stone Africa is published by Mwankom Group Ltd under license from Rolling Stone, LLC, a subsidiary of Penske Media Corporation.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services.

By registering for our sites and services, you agree to our Terms of Service (including, as applicable, the mandatory arbitration and class action waiver provisions) and our Privacy Policy.

We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services.