Historically, African musicians like Fela Kuti and Brenda Fassie used their platforms not just for entertainment, but as powerful tools for activism and change. Their music spoke out against political corruption, oppression, and social injustice, reflecting the struggles of their people. Fast forward to today, and the role of activism in music is once again under debate. This conversation resurfaced in August following an interview with reggae legend Buju Banton on Drink Champs, where he criticised Afrobeats artists for not speaking out enough on social issues.

Banton contrasted today’s Afrobeats musicians with artists like Fela, who used music as a form of protest. “You’re a continent—your words, sounds, and power… and all you are singing is fuckery,” he said on the popular podcast. “You don’t sing a song about freeing Africa at all now.” His comments raise a critical question: Do modern Afrobeats artists have the same social responsibility to address political and social struggles as their predecessors? Or are they facing different pressures that make activism more challenging in today’s globalised music industry?

To understand Banton’s critique, it’s important to consider the legacy of political music in Africa—particularly in Nigeria, where Fela Kuti emerged as a pioneer of both afrobeat and musical activism. Kuti’s music was deeply intertwined with his fight against Nigeria’s corrupt military regimes. On tracks like “Zombie” (1976) and “Coffin For Head Of State” (1980), Fela didn’t shy away from condemning the government, even at great personal risk. His defiance led to brutal repercussions, including the death of his mother, repeated arrests, and the destruction of his property.

Kuti’s bold activism, however, came at a time when African artists did not have the same global exposure or commercial pressures as today’s Afrobeats stars. The stakes were local, and his activism was deeply connected to the liberation of his people. Banton’s idealisation of figures like Fela Kuti reflects a longing for this era of unapologetic musical resistance, but it also raises the question of whether today’s artists are truly failing, or if the landscape has shifted in ways that make activism more complex.

The rise of social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram and YouTube has dramatically expanded the global reach of music, propelling Afrobeats into the global mainstream. However, with this newfound visibility comes a set of challenges that artists in Fela’s time didn’t face. Afrobeats today is not only commercialised but also caters to a more diverse, often Western, audience.

“The wider and more mainstream a genre becomes, the more difficult it becomes to address political issues,” says Will McKinney-Raphelt, Senior Product Manager at RCA Germany x GOLD LEAGUE. Mainstream music, especially in global markets, tends to avoid political themes, and Afrobeats artists risk alienating segments of their international audience by addressing issues that may not resonate universally. The pressures to remain commercially viable in a global market—particularly one dominated by predominantly white demographics—force these artists into a delicate balancing act. This stands in stark contrast to Fela’s regional focus, which allowed him to speak directly to his people without fear of losing international market share.

In this environment, the commercialisation of music—driven by algorithms, trends, and the need for virality—often pushes artists toward more superficial content. When we consider the global, systemic pressures Afrobeats artists face today, Banton’s comments about them not making music with “purpose” seems a little more complicated. While his critique is strong, it overlooks the artists who are using their platforms to speak out against social issues.

Burna Boy, for example, has consistently used his music to address colonialism, systemic oppression and corruption. His 2020-released song, “Monsters You Made”, released during the #EndSARS protests, is a powerful commentary on the violence and systemic racism in Nigeria. Additionally, Burna Boy’s activism extends beyond music—he established the Project Protect fund to support victims of police brutality, demonstrating his commitment to social change.

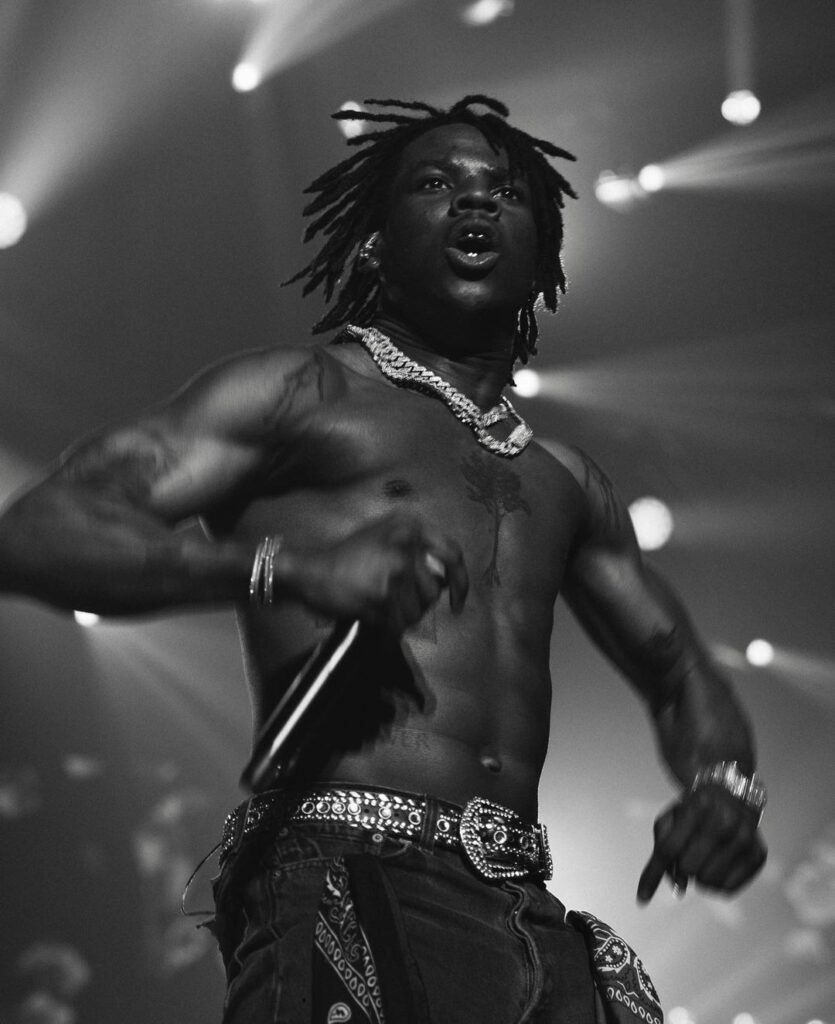

Rema’s 2020 track, “Peace Of Mind”, offers another example: it reflects the emotional toll of societal instability in Nigeria, drawing from real events like the Lekki Toll Gate massacre during the #EndSARS protests. Rema has used his platform to raise awareness about Nigeria’s political struggles, even tweeting that “the world needs to know what is happening here.” These artists contradict Banton’s sweeping generalisations, proving that some in the Afrobeats scene are deeply engaged in activism, despite the risks.

The music industry today operates under a different set of rules than in Fela’s time. Globalisation and commercialisation have created an industry where artists are expected to cater to broader audiences, making it difficult to maintain overt political messaging without facing potential backlash. Many artists are navigating this difficult terrain, balancing their desire for liberation with the need to remain commercially successful.

This isn’t just limited to Afrobeats. In other music scenes, like in Germany, artists like Nura—a Universal-signed artist of Eritrean descent—have spoken out about political issues like the Palestinian conflict, facing tangible consequences such as the cancellation of her shows. Despite the risks, Nura continues to use her platform for activism. “It doesn’t matter to me, the risk to my career,” she said. “I will never stop speaking up for what is right.”

The reality is that today’s artists, particularly those from marginalised communities, are often held to a higher standard when it comes to social and political activism. This pattern reveals a double standard: while white artists can engage with activism on their own terms—often selectively or superficially—Black artists and those from marginalised communities, particularly African musicians, are expected to consistently address the political and social struggles of their audiences. This expectation is both unfair and burdensome, as it adds extra pressure for them to speak out, even when doing so might jeopardise their careers.

With great power comes great responsibility, but how much responsibility should be placed on African artists today? The demands of the modern music industry are relentless, and many artists face the constant pressure to stay relevant in a fast-paced, oversaturated market. With social media algorithms and viral moments often dictating an artist’s success, many find themselves prioritising commercial success over activism.

While some, like Burna and Rema, have chosen to use their platforms to speak out, the expectation that all artists must engage in activism is a heavy burden. “It’s important to use music as a form of expression,” Will McKinney-Raphelt adds, “but music today is very surface-level. Artists shouldn’t be the primary source of information on social issues.” Yet, with influence comes responsibility; artists should at least try to use their platforms to help others, but the decision to engage in activism should ultimately be a personal choice, not an obligation.

In conclusion: Buju Banton’s critique that Afrobeats artists focus on superficial content has merit, but it oversimplifies the complexities of the modern music industry. While there is value in creating music with social and political meaning, today’s Afrobeats artists face different challenges than Fela Kuti did, including global commercialisation and the pressure to appeal to diverse audiences. Activism is not without risks, and the burden of being socially responsible should not fall solely on the artists.

As Nina Simone once said, “An artist’s duty is to reflect the times,” but this should be seen as a choice—not a mandate. Each artist must have the freedom to decide how they use their platform, and while some have chosen to embrace activism, others may not. Ultimately, it’s important to recognise that the responsibility for change should not rest solely on the shoulders of artists but also on the systems that shape their work.

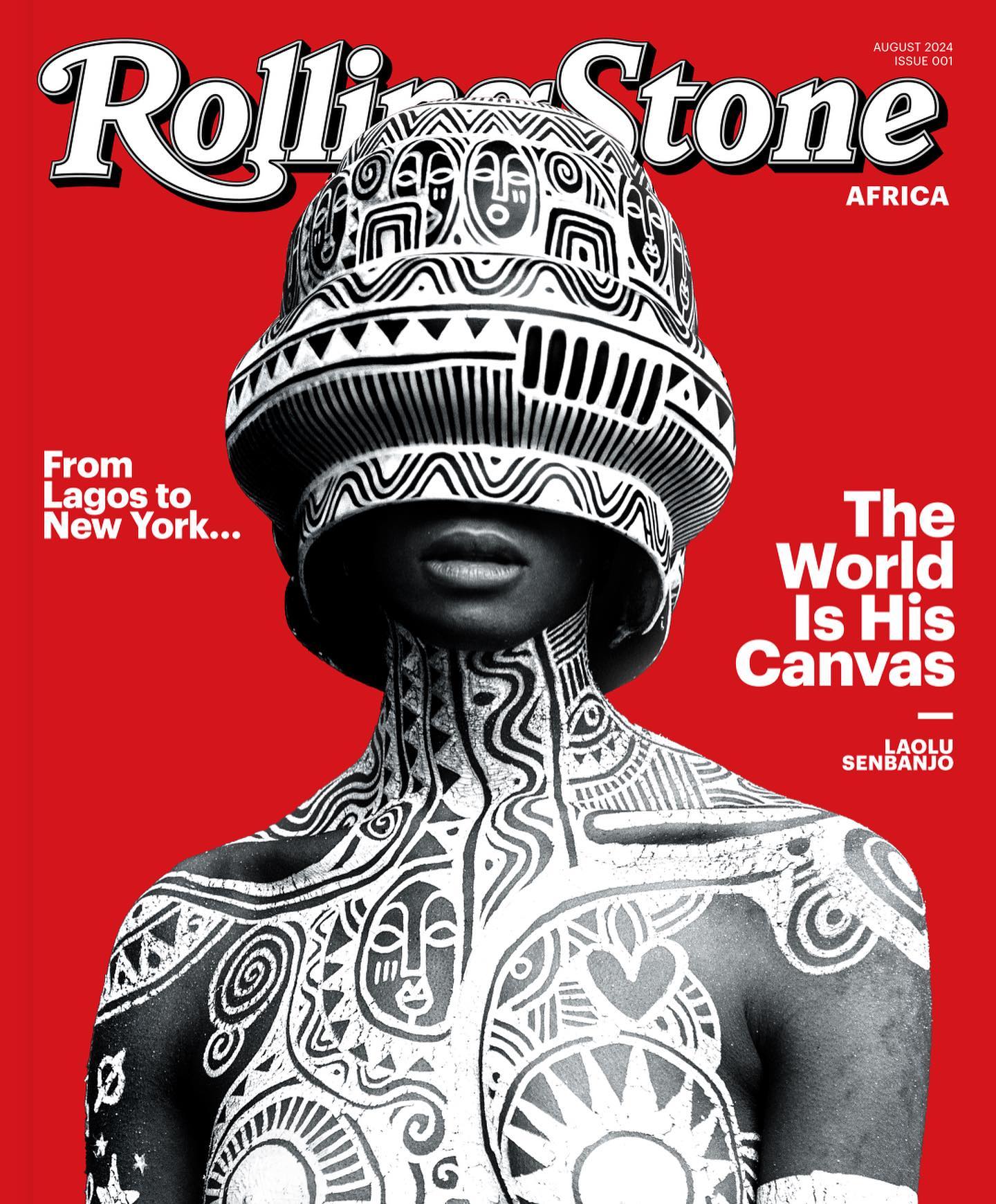

© Copyright Rolling Stone Africa 2024. Rolling Stone Africa is published by Mwankom Group Ltd under license from Rolling Stone, LLC, a subsidiary of Penske Media Corporation.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services.

By registering for our sites and services, you agree to our Terms of Service (including, as applicable, the mandatory arbitration and class action waiver provisions) and our Privacy Policy.

We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services.